ZIMBABWE’S BLOATED EXECUTIVE: A BURDEN ON THE NATION

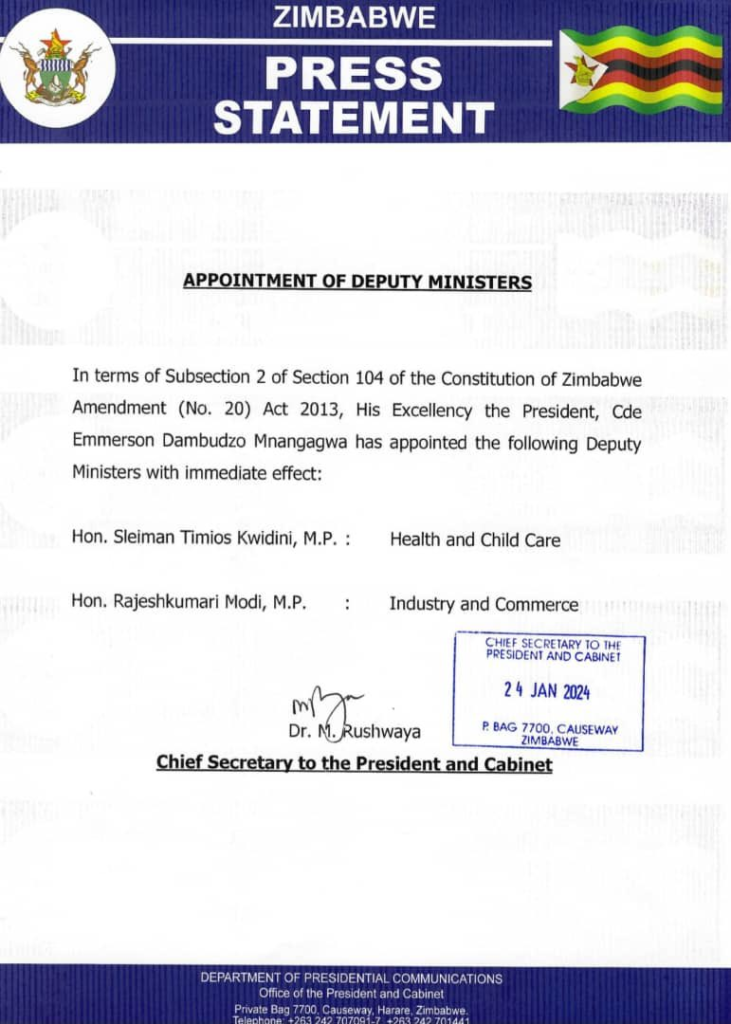

In the latest twist to Zimbabwe’s governance saga, the appointment of two additional deputy ministers has reignited a longstanding debate over the country’s notoriously oversized executive branch. This decision raises fundamental questions about the necessity and efficacy of such roles in a nation grappling with severe economic challenges.

Deputy ministers in Zimbabwe, it’s important to note, do not have the privilege of sitting in the cabinet. They cannot assume the role of acting ministers either, effectively limiting their direct influence on policy and decision-making. Despite these limitations, these officials are entitled to substantial benefits funded by the public. They receive hefty salaries, are provided with luxurious houses and cars, and enjoy various other perks that place a significant burden on the country’s treasury.

The irony of this situation is stark when considering the current state of Zimbabwe’s basic infrastructure and essential services. The nation’s roads are in a state of disrepair, hospitals lack adequate facilities and resources, and schools are far from meeting the educational needs of Zimbabwean children. In this context, the oversized cabinet, along with the deputy ministers, represents a glaring misallocation of scarce resources.

Critics argue that the funds used to sustain this bloated executive could be better directed towards national development projects. Investing in infrastructure, healthcare, and education would not only improve the quality of life for the average Zimbabwean but could also foster long-term economic growth. The current setup, with its emphasis on maintaining a large pool of high-ranking officials, does little to contribute to these critical areas.

Supporters of the government might contend that these deputy ministers play crucial roles in assisting the main ministers and helping to manage the complexities of governing a country like Zimbabwe. However, such arguments are increasingly challenging to justify when the results of such governance are not evidently positive. The presence of numerous deputies has not translated into more effective administration or accelerated development.

The crux of the issue lies in the disparity between the high costs of maintaining the executive and the tangible benefits (or lack thereof) that it brings to the nation. The burden on poverty-stricken taxpayers is substantial. Citizens are expected to finance the lifestyles of public officials whose impact on national development appears minimal at best.

This scenario is not unique to Zimbabwe but is particularly acute given its economic struggles. Many developing countries face similar challenges, balancing the need for effective governance with the realities of limited resources. However, the case of Zimbabwe serves as a stark reminder of the consequences of governmental profligacy.

The debate over the necessity of deputy ministers in Zimbabwe is more than a question of political appointments; it’s a debate about priorities, resource allocation, and the role of government in national development. It also raises broader questions about accountability and the social contract between a government and its people.

In conclusion, the appointment of more deputy ministers in Zimbabwe is a troubling symptom of a larger issue: a governance structure that seems increasingly disconnected from the urgent needs and realities of its people. As long as the executive remains bloated and resources are misallocated, the path to recovery and development for Zimbabwe remains uncertain. It’s time for a critical reevaluation of the role and size of the government, focusing on efficiency and the maximization of limited resources for the greater good of the nation.